US National Parks: A Complete, Up-to-Date Overview – Counts, Designations, and State-by-State Totals

This data-centric guide explains how many US national parks exist, the difference between National Park and the National Park System, and how counts are updated over time. It pulls from official NPS data, provides state-by-state tallies, and links to current lists and datasets, with a documented update cadence.

Key Takeaways

- There are about 433 NPS units in the National Park System, of which 63 carry the formal “National Park” designation.

- The term “National Park System” is broader than the “National Park” designation, and conflating them produces incorrect totals.

- Use the NPS Data Store / IRMA for authoritative counts and always record the dataset URL and access date when citing numbers.

- State tallies commonly list a park in each state it touches, so totals can exceed the number of individual units unless you aggregate by unit ID.

- When counts change, trace the update to the relevant Congressional public law or Presidential proclamation to capture legal provenance.

Grab a cup of coffee and let’s clear up a common question: how many places in the U.S. count as national parks?

The answer isn’t a single number.

There are 63 sites officially named National Park, but the National Park System includes about 433 units of many kinds.

That’s why the list of national parks you see in headlines can differ from the full catalog the NPS maintains. This guide spells out the terms, the counts, and why they keep changing over time.

We’ll dive into how counts are measured and updated—what counts as a unit, what counts as a park, and how designations like monuments or preserves fit in. You’ll learn the current headline totals (433 NPS units, 63 with the official National Park designation), plus region-by-region patterns and state-by-state tallies.

The article also shows exactly where to pull official data, how to verify changes, and how to cite sources so your numbers stay rock-solid in research, teaching, or journalism. And yes, we’ll keep National Park System in view as the broader framework that matters for counts.

Whether you’re planning trips, building a lesson, or writing a policy brief, this piece helps you work with counts you can trust. You’ll get practical steps to access the official datasets, tips for avoiding common mix-ups between “National Park” vs “National Park System,” and ideas for turning numbers into engaging stories.

Sit back, and we’ll map the landscape—from headers to handheld data—so you know what to quote, when to quote it, and how to keep it current.

Overview and Key Definitions

Quick front note before we dive in: when people ask “how many national parks are there?” they usually mean one of two things — the number of places officially named National Park, or the broader count of units managed by the National Park Service.

Both are useful, but they’re not the same thing. This section clears up both terms and explains how official counts get made and refreshed.

National Park vs National Park System: What’s Included

Think of the National Park System as the umbrella and National Park as a single sticker on that umbrella. The National Park Service (NPS) manages hundreds of distinct units — not all of which are called “National Park.” The system currently includes roughly 433 individual units across states, DC, and territories, while only about 63 sites carry the formal name “National Park.” 12

Why the difference? Units in the system use many designations: national monument, national historic site, national preserve, national memorial, national battlefield, recreation area, and more.

Each designation signals something about the resource being protected, the primary purpose (historic, natural, recreational), and sometimes the legal authority used to create it.

Many designations are created by Congress; some (notably many national monuments) can be proclaimed by the President under the Antiquities Act. 3

| Term | What’s Included | Typical Authority |

|---|---|---|

| National Park | Large natural areas with outstanding scenery or ecological value | Usually Congress |

| National Park System | All NPS-managed units (parks, monuments, historic sites, preserves, etc.) | Congress, Presidential proclamation, and administrative designations |

Practical note: when you search for a “list of national parks,” decide whether you need the short list (the 63 named National Parks) or the complete list of NPS units (the ~433 units). Researchers and policymakers usually want the full National Park System counts and categorizations; travelers often mean the named National Parks when planning trips.

How Counts Are Measured and Updated

Counts are not guesswork. The NPS maintains authoritative tallies and descriptive pages that explain designations and system scope. Official totals reflect everything the NPS manages at a given time — and that number changes when a unit is created, re-designated, combined, or (rarely) transferred out. The two big mechanisms that change counts are Congressional legislation and Presidential proclamations (for monuments). 13

- Check the NPS “About the National Park System” and designation pages for the authoritative current totals and terminology. 13

- For granular changes (new park creations and re-designations), look at the NPS news releases and the Congressional bill that enacted the change — those documents explain the legal action that altered the count.

Hidden insight: many public lists you’ll find online quote the same headline numbers, but they can lag behind recent designations. If you need up-to-the-minute accuracy (for research, reporting, or grant work), cite the NPS pages and link to the specific statute or proclamation that created the change. That’s the gold standard for traceability and E-E-A-T.

Quick actionable checklist when you need a verified count:

- Decide which list you need: named National Parks or all NPS units.

- Pull the NPS About/Designations pages for headline numbers and definitions. 13

- For recent changes, find the NPS press release and the Congressional text or Presidential proclamation that authorized the change.

- National Park System (U.S. National Park Service)

- How Many National Parks are There? (National Park Foundation)

- What’s In a Name? Discover National Park System Designations (NPS)

History and Evolution of the National Park System

History and Evolution of the National Park System sits behind every entry in any modern list of national parks. In short: the system began as scattered protections for special places and grew into a federal agency with a wide portfolio of site types and legal authorities.

Below I cover the origins, early parks, and the key milestones that turned a few protected landscapes into today’s National Park System.

Origins and Early Parks

The story starts with individual acts of protection rather than a single master plan. The best-known early move was the establishment of Yellowstone as the world’s first national park in 1872, a landmark decision that set a precedent for protecting landscapes for public use and enjoyment rather than private gain1.

For several decades after Yellowstone, parks and monuments were created piecemeal — sometimes by Congress, sometimes by presidential proclamation — and were managed by a variety of federal departments, which led to inconsistent stewardship and confusion about authority1.

Because early protections were ad hoc, many important places followed different legal paths. For example, some western sites were protected directly by congressional acts while other areas (especially in the East) were acquired through purchases, donations, or state‑federal agreements.

That patchwork approach is why modern counts distinguish between the National Park designation and the broader National Park System of many unit types (parks, monuments, preserves, historic sites, and more).

- Representative early parks and protected places: Yellowstone (first national park), Yosemite and Sequoia (early federal protections that evolved over time), several western volcanic, glacier and canyon parks established in the late 1800s and early 1900s1.

Milestones in Designation and Expansion

Three legal and administrative milestones reshaped the system from scattered places into a coordinated national program:

| Year | Event | What changed | Why it matters |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1872 | Yellowstone designation | First park set aside by Congress | Established the idea of protection for public enjoyment rather than private use1 |

| 1916 | Organic Act — creation of NPS | Congress created the National Park Service within the Department of the Interior | Provided a single agency and statutory mission to conserve scenery and historic objects and provide for public enjoyment2 |

| 1933 | Federal reorganization | Consolidated federally owned parks, monuments, memorials and other sites under NPS | Greatly expanded the Service’s authority and the range of unit types managed by NPS3 |

After 1933 the system continued to grow through legislation, executive action, land acquisitions, and cultural-site designations.

By the late 20th century, environmental laws and rising public interest broadened NPS’s role to include scientific research, historical preservation, and recreation management; today the Service manages hundreds of units in many designations, not just the classic “national park” label used in casual lists of national parks2.

Hidden insight: when you consult any contemporary list of national parks, remember that the NPS manages many more unit types than the word “park” implies. That’s why authoritative counts and state tallies come from official NPS lists and their versioned datasets rather than casual summaries.

Practical tip: For researchers or educators wanting the official, up‑to‑date list of national park units (and to avoid mixing “park” vs “system” counts), use the National Park Service data pages and the historical timelines linked below — they’re the authoritative source for designation dates and legal milestones2.

- “Brief History of the National Parks,” Library of Congress

- “History of the National Park Service,” National Park Service

- “NPS Centennial: System Timeline,” NPSHistory

Official Sources and Data Provenance

Below are the authoritative sources and practical rules I use when compiling any official “list of national parks” or state-level tallies. This section explains who publishes the canonical records, where to find downloadable datasets, and how to track changes to counts over time.

Primary Authorities: NPS and Government Lists

When you need an official source, start with the National Park Service (NPS). The NPS maintains the central data repositories used by researchers, educators, and policy analysts: publications and data landing pages that link to park-level pages, GIS boundaries, and visitor statistics⁽¹⁾. For geospatial files and systemwide tables the NPS science pages and data stores are the practical hubs—these include metadata, last-updated dates, and common download formats like CSV and ESRI shapefiles⁽²⁾.

- What NPS provides: park pages (Find a Park), Data Store/IRMA archives, NPSpecies, and technical reports with dataset metadata⁽¹⁾.

- What federal portals provide: Data.gov and the federal catalog aggregate many NPS datasets and show publisher metadata, update frequency, and direct downloads from the DOI/NPS publisher record⁽³⁾.

Quick tip: treat NPS web pages and Data.gov entries as primary evidence of the current lists and boundaries. When a legal change occurs (a new park is designated or a unit’s status is changed), the legal authority is the Congressional public law or a Federal Register notice—these live outside NPS but are the legal provenance of any designation⁽4⁾.

Versioned Counts, Changelogs, and Citations

Counting parks sounds simple until you realize counts change, unit names shift, boundaries are revised, and new designations are created by Congress. There is no single unified public changelog that lists every park-addition or status tweak in one place. Instead, provenance is reconstructed from dataset metadata, NPS press releases, and legislative records⁽1⁾⁽3⁾.

| Resource | What it shows | How to cite |

|---|---|---|

| NPS Data Store / IRMA | Dataset tables, GIS boundaries, metadata and last-updated | Title, NPS, dataset DOI or URL, access date⁽1⁾ |

| Data.gov (NPS catalog) | Cataloged datasets with publisher metadata and downloads | Data.gov entry URL, dataset name, publisher, access date⁽3⁾ |

| Congress.gov / Federal Register | Legal acts creating or changing designations | Public law number or Federal Register citation, date⁽4⁾ |

Actionable steps to preserve provenance:

- Always record the dataset name, publisher (NPS/DOI), exact URL and the access date when you pull a table or boundary file.

- Use dataset metadata (look for a DOI or version string). If none exists, snapshot the page (archive.org) and save the dataset file with a timestamped filename.

- When a count changes, trace it back to an NPS press release or a public law on Congress.gov to capture legal provenance; include the law number in your notes⁽4⁾.

- For reproducible research, publish a short changelog: dataset source, version/date, and the rule you used (e.g., “count includes only units designated ‘National Park’ as of 2025-07-01”).

Hidden insight: many users confuse the National Park System (all NPS units) with the specific subcategory “National Park.” If you’re publishing a state-level tally or a “63 national parks” style headline, state explicitly which list and dataset you used and the snapshot date—so readers and reviewers can verify your claim⁽2⁾.

- Publications (U.S. National Park Service)

- Data Sets and Tools – Science (U.S. National Park Service)

- National Park Service – Dataset – Catalog (Data.gov)

- Congress.gov — search public laws and statutes

Current Counts by Designation

Quick recap from earlier sections: the National Park System is a single administrative family of sites, but not every NPS site is a “National Park” by name. Below we walk through the current headline counts, how designations are grouped, and the common confusions that trip up researchers and travelers alike.

Total National Parks Through the Latest Version

The simplest, most-cited headline: the National Park Service currently administers 433 units (park sites) in the National Park System1. Of those, 63 carry the formal “National Park” designation — the ones most people picture when they say “national parks” (think Yellowstone, Grand Canyon, Everglades)12.

Those totals are maintained and updated by NPS; additions, renames, and re-designations appear in the agency’s changelog so researchers can track the latest versioning and legislative changes3. If you need a one-line answer for a presentation or syllabus, say: 433 NPS units; 63 official National Parks (and then link to the live NPS list so readers can verify the date).

| Metric | Current value | Why it matters |

|---|---|---|

| Total NPS units (all designations) | 4331 | Complete administrative universe for the National Park Service |

| Units with the official “National Park” title | 6312 | Subset commonly referred to as “national parks” in travel guides |

| Named designations in use | At least 19 types1 | Shows the diversity of site roles (monuments, preserves, historic sites, etc.) |

Counts by Designation Type (Park, Monument, Preserve, etc.)

Here’s the rub. While the NPS publishes the master list of its units, it does not maintain a single, easy-to-read table on the public site that lists every designation with a precise, up-to-the-minute count for each type in one place. Many trusted summaries will repeat the headline numbers (433 and 63) but stop short of a full per-designation breakdown in a single table12.

That said, the system uses roughly 19 naming designations (for example: National Monument, National Preserve, National Historical Park, National Historic Site, National Seashore, National Lakeshore, National Recreation Area, National River, National Battlefield, and more) and those cover very different legal purposes, sizes, and management rules1. If you need counts by type for a report, the most reliable approach is to pull the NPS dataset or filter the NPS “Find a Park” search by designation (methods shown below).

- Quick method: Use the NPS “Find a Park” or agency data/API to filter by designation and export a CSV (this produces authoritative, reproducible counts).

- Why not rely on static lists: Third-party articles often quote slightly different totals because they snapshot the list on different dates.

Understanding Unit vs. Park Totals

Confusion about counts usually comes from terminology. Here’s a friendly breakdown you can copy into your notes:

- Unit: Any site administered by the NPS. This is the administrative, catch‑all number — the 433 figure1.

- National Park (designation): A legal title given to a specific subset of units. These are the 63 places formally named “National Park” (not every beloved NPS site has this title)12.

- Other designations: Monuments, preserves, historic sites, seashores, and more — each reflects different founding laws and management goals, and they are all “units” of the system even if not called a “park”1.

Practical tip: when you write or teach, always qualify which count you mean. Say “63 National Parks” when you mean the formal designation, and “433 NPS units” when you mean the whole system. If you need programmatic counts, the NPS site and changelog provide the best primary data and version history to cite3.

- National Park System (U.S. National Park Service)

- How Many National Parks are There? (National Park Foundation)

- Recent Changes to the National Park System (National Park Service)

State-by-State Totals: A National Snapshot

Now that we’ve defined what counts as a ‘national park’ and where those counts come from, it helps to zoom out and see how those units are distributed across the country. Below I break the nation into readable pieces: regional patterns, the states that lead the pack, and exactly how you can pull state-level data yourself.

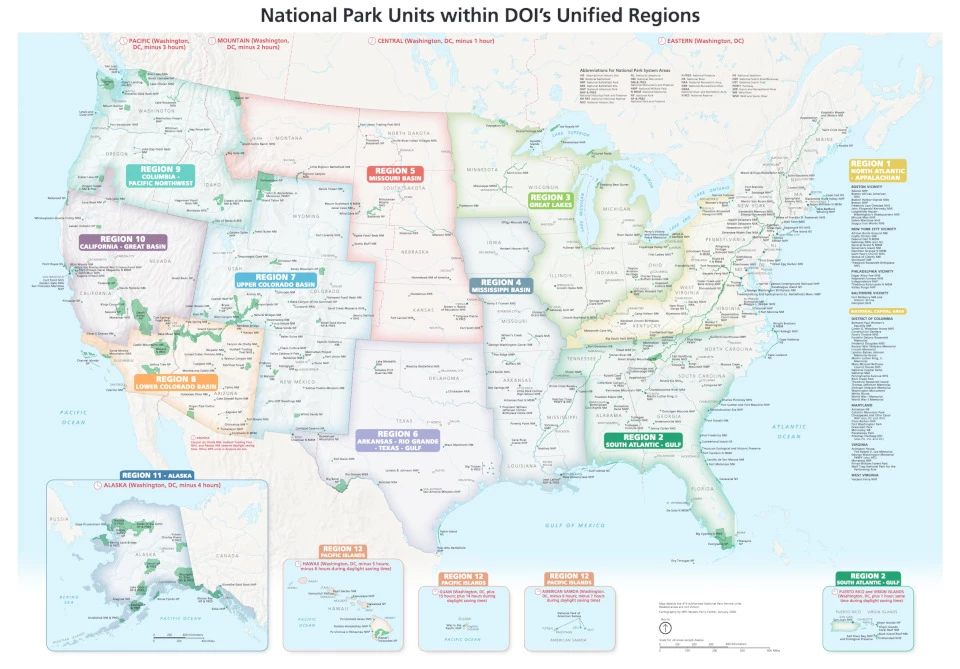

Region-by-Region Breakdown

National parks are heavily concentrated in the U.S. West. The Pacific and Mountain regions contain the majority of parks, thanks to clusters in California, Alaska, Utah and Arizona; by contrast, the Northeast and parts of the Midwest have comparatively few federally designated national parks. This West-heavy pattern shows up in nearly every catalog and table you’ll find because the landscapes that receive ‘park’ status—vast wilderness, iconic canyons, big mountain ranges—are more common there.12

Two quick, practical things to remember about regional counts: first, a park that spans multiple states (for example, Yellowstone or Great Smoky Mountains) will usually be listed for each state it touches. That means regional and state tallies can add up to more than the total count of individual parks. Second, regions are useful for planning travel or curriculum (group parks by similar ecosystems and management issues), but they’re not official NPS categories—regions are a human-friendly lens, not a legal one.2

States with the Most Units

If you’re wondering where to go to tick off a bunch of parks, here are the top states by number of national parks. These totals come from consolidated listings that count a park in each state it occupies, which is the standard approach for state-level tallies.

| State | # of National Parks | Notable parks (examples) |

|---|---|---|

| California | 9 | Yosemite, Sequoia & Kings Canyon, Death Valley |

| Alaska | 8 | Denali, Glacier Bay, Gates of the Arctic |

| Utah | 5 | Zion, Bryce Canyon, Arches |

| Colorado | 4 | Rocky Mountain, Mesa Verde |

| Arizona | 3 | Grand Canyon, Petrified Forest |

Source summaries consistently show California leads, followed by Alaska, with Utah and Colorado also high on the list. Use this as a quick orientation—the exact totals can vary slightly between sources depending on update timing and whether territories or other NPS unit types are included.12

How to Access State-Level Datasets

If you need authoritative, machine-readable state-level counts (for research, teaching, or planning), don’t rely solely on static tables. Here’s a simple, repeatable workflow to get official data:

- Start at the NPS IRMA Data Store and search for ‘parks’ or ‘units.’ The IRMA store hosts CSVs, reports and shapefiles used by researchers and planners.4

- Check the NPS data access & APIs page for programmatic endpoints and data documentation if you want to pull updates automatically.5

- If you only need a quick reference table, Wikipedia and consolidated rankings (World Population Review) provide ready-made state tables, but always cross-check with NPS for the latest official status and boundary definitions.12

Hidden insight: always check whether a source counts only ‘National Parks’ (the formal designation) or all NPS units (monuments, historic sites, preserves). Mixing those will give you confusing totals. Also watch for update dates—the NPS may reclassify or add units, and third-party sites may lag behind the official changelog. Pro tip: when you download a dataset, look for state FIPS or polygon attributes so you can reliably aggregate parks by state without double-counting shared units.

- “National Parks by State 2025,” World Population Review

- “List of national parks of the United States,” Wikipedia

- “U.S. States With the Most National Parks,” MyFinancingUSA

- NPS IRMA Data Store (official data products)

- NPS: Data access and APIs

Comprehensive Lists and Official Listings

If you want a single authoritative “list of national parks” for research, citation, or trip planning, the official catalogs come from the National Park Service and its open-data portals. Below I point you to the canonical lists, explain what each file contains, and give simple steps to download the exact dataset you need.

Official Comprehensive List of National Parks

The National Park Service maintains the definitive roster of all NPS units, which includes national parks along with monuments, historic sites, recreation areas, preserves, and other designations. That master listing is the place to start when you need an official count or want to confirm whether a site is legally designated as a “national park” or a different unit type. Remember: the phrase “national park” is a specific designation and only a subset of the broader National Park System, so always check the unit type field in the official record rather than assuming from common usage1.

Practical steps to use the official list:

- Open the NPS unit index or park finder and search by name or state to see the unit type, web page, and contact info2.

- For research, download the machine-readable park units dataset from the NPS open data portal or IRMA to get standardized fields (unit name, designation, state(s), year established, and identifiers) that are easy to filter programmatically3.

- When citing counts in reports, include the dataset version or retrieval date because Congress can create new units and the NPS updates records periodically4.

Direct Links to Datasets and Listings

Here are the most useful official sources and what you can do with each one. Click any link to open the live, authoritative file.

- FindYourPark — Park Finder, searchable public index good for quick lookups and trip planning2.

- NPS Open Data (ArcGIS), downloadable park-units datasets, shapefiles, and GeoJSON for mapping and spatial analysis3.

- NPS Maps & GIS, official park maps and guidance for boundary files and cartography use1.

- NPS Database and Research, useful for authoritative documents and archival records that support legal and historical status5.

- USA.gov — National Park Service, central government page linking to agency resources and data portals4.

| Dataset / Listing | Source | Formats | Best for |

|---|---|---|---|

| Park Units (master list) | NPS Open Data | CSV, GeoJSON, Shapefile | Counts by designation, state tallies, programmatic filtering |

| Official Park Pages | FindYourPark / NPS | HTML | Visitor details, park contacts, activities |

| Maps and Boundary Files | NPS Maps & ArcGIS | Shapefile, KML, GeoJSON | GIS analysis, area calculations, mapping |

Hidden insight and a common pitfall: many external lists and travel sites conflate “NPS units” with “national parks.” For precise academic or policy work, always use the official park-units dataset and record the retrieval date. If you need legislative authority or historic designation text, pair the dataset with the NPS database and CRS reports to capture the legal basis for a unit’s status5.

- “Maps (U.S. National Park Service),” NPS

- “Park Finder,” FindYourPark

- “Public NPS Open Data,” ArcGIS

- “National Park Service,” USA.gov

- “National Register Database and Research,” NPS

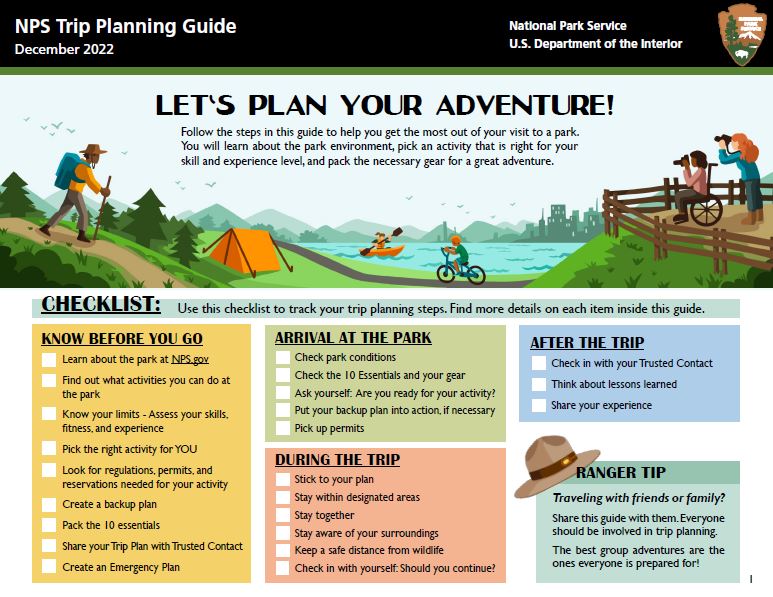

Planning and Practicality: Researchers, Educators, and Travelers

If you use a “list of national parks” in work or play, you want numbers that are current, context that’s accurate, and tips that actually save time on the ground. Below are practical ways researchers, educators, and travelers can turn official counts and visitation data into safer, smarter projects and trips.

Using Counts for Research and Curriculum

Official NPS counts aren’t just trivia — they’re primary data you can build lessons and analyses on. The NPS publishes detailed visitor-use categories (recreation vs. non-recreation, overnight types, visitor hours) that let you compare parks by use intensity, seasonality, and visitor behavior for classroom labs or papers. For reproducible research, pull data from IRMA Stats or the NPS visitation reports and snapshot the dataset date in your methods so others can reproduce results.

Practical classroom idea: have students build a mini research project comparing two parks’ month-by-month visits to test hypotheses about climate, accessibility, or proximity to cities. Use historical lists and the official counts to show how the “number of national parks” and unit classifications change over time — it’s a way to teach both statistics and civics.

- Quick steps for researchers/educators: download IRMA CSVs, document the dataset version, filter by park unit ID, and visualize monthly trends.

- Common pitfall: treating national totals as equally representative; some units don’t report and small sites can skew averages.

Accessibility and Safety Across Parks

Accessibility and safety are site-specific. NPS visitation datasets support resource managers planning crowd control and emergency staffing but don’t replace park-level accessibility pages or ADA guides. Use counts to identify high-traffic months (so you can request extra accommodations or emergency planning) and always confirm details directly with the park you plan to visit.

Best Times to Visit and Data-Informed Itineraries

If you’re planning an itinerary, let the data nudge you off the beaten path. Recent NPS summaries show visitation patterns shifting outside the traditional summer peak; many parks now see above-average visits in shoulder months such as spring and fall. Use monthly visit data to avoid peak days and plan for services.

Itinerary tips: travel mid-week in shoulder months if you want fewer crowds; for remote parks, plan for limited services regardless of visitation numbers. If your goal is to see many parks, combine small nearby units on lower-visit days rather than trying to hit major parks during peak weekends.

Hidden insight: national totals can mask local pressure. A national increase in visits doesn’t always mean every park is busier. Check park-level month-by-month counts before booking — it saves time and reduces safety risks.

Passes, Fees, and Access

If you’re using the list of national parks to plan trips or school projects, understanding passes and fees makes a huge difference — both for budgeting and access. Below are the main pass options, who qualifies, where they work, and practical tips that most top pages don’t call out clearly.

Overview of Pass Options

The backbone for visiting federal lands is the America the Beautiful Interagency Pass, a single pass that covers entrance and standard day‑use (amenity) fees at more than 2,000 federal recreation sites across multiple agencies. It’s the best first purchase for frequent visitors because it simplifies entry across many NPS units and other federal lands⁽¹⁾.

- America the Beautiful Annual Pass — standard interagency annual pass (price stated below)⁽¹⁾.

- Senior Pass — lifetime or annual reduced option for U.S. citizens or permanent residents age 62+⁽²⁾.

- Access Pass — free lifetime pass for U.S. citizens or permanent residents with permanent disabilities⁽²⁾.

- Military Pass — free annual pass for active duty military and dependents (some parks issue lifetime at the gate)⁽¹⁾.

- Fourth Grade / Youth Passes — free passes (Every Kid Outdoors/Fourth Grade) for eligible youth for a school year — exchange or redeem per agency rules⁽¹⁾.

- Site‑specific and seasonal passes — daily, weekly, or seasonal passes sold for individual parks or areas; many are available digitally via Recreation.gov⁽³⁾.

| Pass | Typical Cost | Who | Coverage |

|---|---|---|---|

| America the Beautiful | $80/year (standard) | Anyone 16+ | Entrance & standard day‑use at ~2,000 federal sites (NPS, USFS, FWS, BLM, BOR, USACE)⁽¹⁾ |

| Senior Pass | $80 lifetime / $20 annual | Age 62+ | Same federal coverage as interagency pass⁽²⁾ |

| Access / Military | Free (with documentation) | Disabled veterans / active military | Same federal coverage; verification required⁽²⁾ |

Eligibility, Costs, and Where Passes Apply

Here’s what matters when you’re deciding which pass to buy. First, most federal passes cover entrance and standard day‑use fees at NPS units and other federal recreation lands, but they usually do not cover expanded amenity fees such as camping, special tours, or concession services (boat rentals, guided trips)⁽¹⁾. That’s an easy pitfall — you might still pay for a campground or a boat tour even with a pass.

Second, federal passes generally do not cover state park entrance fees unless a state program specifically participates or there is a regional/statewide pass that includes both state and federal sites. Those regional passes are relatively rare and often sold locally (for example, coastal or multi‑park regional passes)⁽³⁾.

Practical tips:

- Buy the America the Beautiful pass if you plan to visit multiple parks in a year — at about $80 it often pays for itself after two or three paid entries⁽¹⁾.

- Bring documentation for special passes (senior ID, military ID, disability forms) — some passes require in‑person validation to get the physical card⁽²⁾.

- Check for fee‑free days before travel; parks announce them annually and they waive entrance fees for everyone⁽¹⁾.

- When planning from the article’s list of national parks, cross‑check each park’s site page for local fees and reservation rules — some parks require timed entries or have campsite reservation windows separate from entrance passes⁽³⁾.

Hidden insight: digital and site‑specific passes on Recreation.gov are increasingly common and instant — but they coexist with traditional printed passes. If you prefer a physical card for quick gate access, request it when redeeming vouchers or buy at a park information desk⁽³⁾.

- “Entrance Passes (U.S. National Park Service),” NPS

- “Federal Recreation Passes,” U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service

- “Buy a Pass,” Recreation.gov

Educational Narratives and Storytelling

Data about parks—counts, designations, species lists, and historical reports—only becomes meaningful when you stitch it into a human story. Below are practical ways to turn the official list of national parks and related datasets into teaching moments, visitor experiences, and community-driven narratives that build on the counts and definitions described earlier.

Connecting Data to Park Stories

Start with a single, authoritative dataset (for example the NPS unit list or a state tally) and ask: what personal, ecological, or cultural story does this number hide? Numbers become memorable when anchored to people and place. Use these steps:

- Pick a datum and a question. Example: if the state tally shows three national parks in Utah, ask what different ecosystems each protects and which communities steward them.

- Pair data with primary sources. Combine official counts with oral histories, historical maps, and scientist field notes to give depth to the figure you quoted. This shows how the “how many” connects to “why it matters.”1

- Translate charts into narratives. Convert a table of visitation trends into a seasonal story (“spring wildflowers bring students; winter solitude attracts researchers”) and use simple visuals to make trade-offs clear.

- Honor multiple perspectives. Integrate Indigenous histories, local archives, and community voices so the story reflects more than the designation on a federal list.3

Hidden insight: small, system-level counts (like “63 national parks”) are great headlines, but educators get the biggest impact by zooming in: one park, one community, one dataset. That’s where curiosity sticks.

Case Studies and Educational Resources

There are real-world models you can copy. The National Park Foundation’s Inclusive Storytelling grants fund interpretive updates and curricula that bring marginalized perspectives into park narratives. Those projects demonstrate how grant-backed resources become classroom-ready modules and exhibit content.13

Another example: digital storytelling workshops connected youth and elders at civil-rights-era sites, producing first-person audio and video that now live alongside official exhibits and lesson plans—perfect for classroom case studies that bridge the official park list with lived experience.5

| Resource | Best use | How to access |

|---|---|---|

| Inclusive Storytelling Grants | Funding for curriculum and exhibit updates | Apply via National Park Foundation announcements1 |

| Theme/context studies | Background research to inform tours and lessons | Use NPS planning and history publications2 |

Practical classroom activity (ready-to-run): pick one park from the official list, locate two datasets (visitor counts and a species list or a historical timeline), interview a local expert or use archived oral histories, then ask students to produce a two-minute narrative or 1-page interpretive panel that links the data to human experience. This creates a quoted, evidence-based story they can cite in reports or presentations.

Common pitfalls and how to avoid them:

- Avoid relying solely on static webpages. Check changelogs and versioned counts before citing a number; park designations and unit statuses can be updated over time.2

- Don’t treat community memories as mere color—validate sources, get permissions, and co-create interpretation with rights-holders.5

- Beware of over-simplifying sensitive histories; use context studies and NPS guidance to frame difficult topics responsibly.2

Want funding or partners? Contact the National Park Foundation and local NPS interpretive staff early—many parks now prioritize inclusive projects and provide templates or matching funds for educational programming.1

- National Park Foundation: Inclusive Storytelling Program (press release)

- Planning for a Future National Park System (NPS history publication)

- NPF: New Round of Funding for Inclusive Storytelling

- Research in the Parks (NPS proceedings)

- StoryCenter: NPS Case Studies (Digital Storytelling)

Donations, Partnerships, and How to Support the System

Money, partnerships, and everyday volunteers are what keep the National Park System running beyond the line items in a congressional budget. Below we unpack who pays for what, how park partners fit into the picture, and practical ways you can give or verify impact.

Funding Roles and Partnerships

Think of park funding as three overlapping buckets: federal appropriations (the backbone), national philanthropic partners (the scaling engine), and local park partners or concessionaires (the on-the-ground boosters). The National Park Service receives federal funds for core operations and staffing, but philanthropic groups—particularly the National Park Foundation—fill gaps for projects, visitor programs, and urgent maintenance needs. The National Park Foundation is the official charitable partner of the NPS and supports hundreds of parks through targeted grants and national initiatives⁽1⁾.

Who does what — a quick table:

| Funder | Typical Role | How you interact |

|---|---|---|

| Federal (NPS) | Core staffing, law enforcement, basic maintenance | Tax-funded; you influence via policy and representatives |

| National Park Foundation | National grants, major fundraising campaigns, program scale-up | Donate online, join membership, give to campaigns⁽2⁾ |

| Local park partners / Friends groups | Park-specific projects, volunteer programs, education | Donate locally, volunteer, attend fundraisers; many publish impact reports⁽3⁾ |

Park partner organizations collectively contributed substantial funding to NPS projects in recent years, demonstrating how critical philanthropy is to park programming and capital work⁽3⁾. Concessionaires and corporate partners can also provide funds, in-kind services, or matching gifts for specific visitor-facing projects. A lot of the innovation in visitor services and educational programming comes from these partnerships.

How to Contribute and Access Impact Reports

Want to make sure your gift does what you expect? Here are practical, trustworthy steps that I use when deciding where to donate.

- Choose the right recipient. If you want national scale, give to the National Park Foundation. If you want a visible change at one park, give to the park’s official Friends group or the park’s own donation portal⁽2⁾.

- Pick the gift type. Options include one-time gifts, monthly sustaining donations, restricted gifts for a specific project, planned giving, and in-kind support. Matching gifts and donor-advised funds are common ways to amplify donations.

- Verify transparency. Look for annual reports, audited financial statements, and charity ratings. The National Park Foundation publishes annual and audited financial reports and highlights transparency credentials on its site⁽2⁾.

- Check local impact reports. Many Friends organizations and regional park funds publish annual or impact reports describing the exact projects funded and outcomes achieved. These are invaluable for seeing your dollars at work⁽4⁾.

- Volunteer or combine giving with time. If you can, pair a donation with service. Volunteers amplify impact and many park partner groups coordinate volunteer projects.

Quick checklist before you hit donate:

- Is the gift restricted or unrestricted?

- Does the organization publish recent audited financials?

- Are there local impact reports showing project outcomes?

- Is there a matching gift program you can use?

Finally, if you’re a researcher or educator using park counts and designations from earlier sections of this guide, remember that funding sources often align with park priorities. Knowing whether a park relies heavily on philanthropic dollars can explain why some parks have more interpretive programs or faster project completion than others. Look for the National Park Foundation’s giving details and partner reports for national context, and the local Friends group reports for park-level evidence of impact⁽2,3,4⁾.

- National Park Foundation — How You Can Help

- National Park Foundation — Financial & Annual Reports

- NPF — Park Partner Community / 2024 Park Partners Report

- Washington’s National Park Fund — 2024 Impact Report

Wrapping Up

Quick recap: this guide clarifies what counts when people ask for a list of national parks by separating the National Park System from the National Park designation, and shows how official tallies are updated. There are about 433 NPS units across the system, with 63 carrying the formal title “National Park.” Counts shift when new designations or proclamations come through, so sticking to the authoritative NPS designation pages and data stores (and citing the exact statute or proclamation) keeps your numbers trustworthy.

Takeaway: when you cite counts, use official datasets and record the retrieval date so your numbers don’t drift. A quick next step is to check the NPS data store or FindYourPark before you write, drop in a live link to the precise designation, and you’ll save readers time and confusion. If you want a friendly nudge, bookmark the NPS “About the National Park System” page for ongoing updates—that little extra accuracy makes a big difference on any trip, report, or lesson.

- Key Takeaways

- Overview and Key Definitions

- History and Evolution of the National Park System

- Official Sources and Data Provenance

- Current Counts by Designation

- State-by-State Totals: A National Snapshot

- Comprehensive Lists and Official Listings

- Planning and Practicality: Researchers, Educators, and Travelers

- Passes, Fees, and Access

- Educational Narratives and Storytelling

- Donations, Partnerships, and How to Support the System

- Wrapping Up

Get your FREE Monstera Art download

Join our WanderLife Studios mailing list to get updates about our work and be the first to know about upcoming art products.

As a Thank You Gift, you will get this wonderful hand-drawn Monstera Line Art as a digital download for FREE .